Preparing for return to sport...

Principles of Skill Acquisition

Meagan Davis

15 SEPTEMBER 2020 | PREVENTION

With sport looking to make a come-back, it’s a good time to take a closer look at motor learning and skill acquisition. Understanding these concepts will be integral for guiding and accelerating everyone back to their activities.

Motor skill refers to achieving a goal through the voluntary control of joints and body segments, in order to produce a movement. 4 If we take shooting proficiency in basketball for example, the study of motor learning provides the foundation for how this skill is acquired and performed.

MOTOR LEARNING THEORIES

In this next section, we are going to take a look at two motor learning theories, which are important for understanding skill acquisition. One thing that has us stumped…..how do we produce a coordinated pattern, by moving our body in one or more planes (degrees of freedom)? 4 The following two theories help solve the motor problem by taking into account the nervous system.

Motor learning theory 1 - The Schmidt’s Schema Theory.

The first concept is The Schmidt’s Schema Theory. This idea looks at how the movement pattern is produced. Ultimately, there’s a set of motor commands, which are stored and retrieved from memory, and then adapted to a particular situation. 5 If we take walking as an example, we don’t consciously think about dorsiflexion or plantarflexion at the ankle. As this motor pattern is pre-programmed and stored in the long-term memory and then drawn down to the lower centres when required. This theory has more of a top-down information sharing approach.

Motor learning theory 2 - The Dynamical Systems Perspective Theory

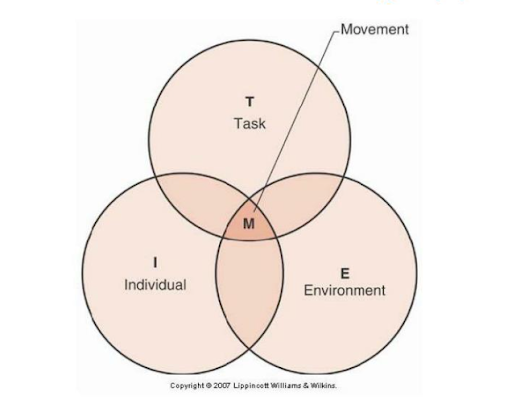

The second concept we are going to look at is The Dynamical Systems Perspective. Yes, It’s a bit of a mouthful, but it’s a good framework for modelling athletic performance. This theory looks at how Individual, Task and Environment, cooperate and self-organise to produce the movement. This concept has more of a lateral information sharing approach.6

Below are the 3 factors, which dictate how the movement pattern will be performed:

Individual – Weight, height, cognitive, current skill level

Task – rules of the game, goal of the task, equipment used

Environment – temperature, light, wind, crowd noise

So how does it work, if there’s no leader? The point at which all 3 circles overlap is known as the ‘attractor state’ or ‘stable state’. This is achieved when we are very comfortable with the skill and can also execute it well. When we are pushed outside of this stable state, by one or all 3 of the constraints, the current movement pattern is forced to change, and a return to stable state is only achieved once the new pattern/technique is assumed.6

Highly skilled athletes have great agility in adapting to the variability of these 3 constraints, in order to maintain a stable state during sports performance. The more efficiently an athlete can adapt to the variability during a game/event, the faster the athlete will return to the stable state and athletic performance will be produced.

Let’s take kicking a soccer ball for example. You first learn to kick the ball by placing it on the ground and kicking it with your foot. The only constraint is the Individual’s skill level. However, with enough practice the skill will improve. A change in stable state occurs, when a ball is passed between team-mates during a match. There is now a change in the Task - with opponents approaching on the field. There is also a change in the Environment - as the distraction of crowd noise is a factor. And finally, there is also a change to the Individual - as skill level is being challenged, the movement pattern must be reorganised, to accommodate the change in the 3 constraints, to perform the skill successfully. The faster a soccer player can overcome these changes, the quicker the athlete will return to a stable state, and the more elite the athletic performance will be.

Now we understand the theories behind motor learning, it’s time to see how the stages of motor learning help shape skill acquisition.

SKILL ACQUISITION

At a higher level, our understanding of what exactly is acquired during skill acquisition, remains to be a fairly ‘broad-brush’ style approach to the concept. We have theories and clinical application of teaching a skill, however we don’t know what practices are best for developing these skills. 1

STAGES OF MOTOR LEARNING

There are many different theories on the stages we go through, when learning a motor task. In this blog, we are only going to look at two of them.

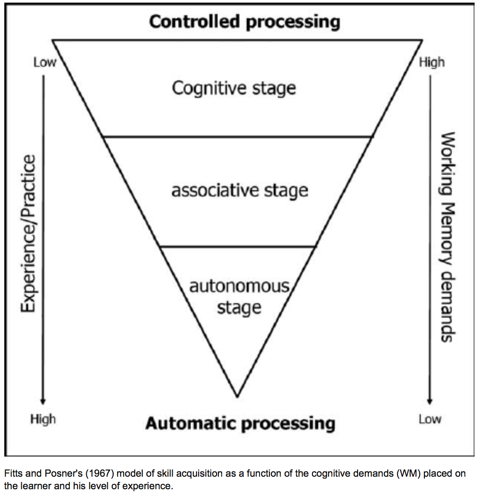

First, we have Fitts and Posner (1967) who developed the 3 stages of motor learning. 2

Cognitive stage:

- Goal: Understand the task.

-

Key components of the stage:

- Significant improvement in the skill; large number of errors and; complete attention to the coaching cues.

Associative stage:

- Goal: Comprehend and perform the mechanics

-

Key components of the stage:

- Performance starts to improve relative to amount of practice; Decreased number of errors and; the individual can associate specific cues with movement patterns

Autonomous stage:

- Goal: Perform the task with speed, efficiency and precision

-

Key components of the stage:

- The skill has become automatic/no longer requires conscious thought. Self-learning from mistakes to adjust and improve performance

Second, Ann Gentile (1972) developed the two-stage progression model. 3

This was a more goal directed approach to motor learning.

Stage 1: Initial Stage involves achieving 2 goals.

- Goal 1: Acquire the movement pattern through developing coordination

- Goal 2: Discriminate between regulatory and non-regulatory movements

Stage 2: Later Stage

- Goal: Adapt the movement pattern, increase consistency and perform the movement with economy of effort.

Coordination is stored in the long-term motor memory and for continuous skills like running and swimming, we see that these skills remain near perfect for decades. For skill-based sports, you’ll remember how to execute the activity for a long time, but the accuracy and diversity of the skill will be lost. The challenge comes from keeping the touch/timing/reactive ability when you stop working on specific sports skills. To put this simply, the overall motor skill remains intact, but the body’s ability to execute the activity well, becomes unpractised and needs to be sharpened. 1 4

Practical Application

While this blog has looked at the physical environment and the physical capacity of the individual, is it very important we look to add the impact of Psychological factors on skill acquisition. Clinicians and coaches should be motivated to understand how important this brain-behaviour relationship is, as it is the foundation of how we move. We still need the rehab, strength + conditioning and recovery; however, skill acquisition is a critical piece to the performance puzzle.

-

Araújo, D., & Davids, K. (2011). What exactly is acquired during skill acquisition?. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 18(3-1), 7-23. https://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/10054163/araujodavids2011_jss.pdf?AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAIWOWYYGZ2Y53UL3A&Expires=1531669718&Signature=SeSxTzz8deIlGugHdYxCun5MJ4A%3D&response-content-disposition=inline%3B%20filename%3DWhat_Exactly_is_Acquired_During_Skill_Ac.pdf

↩ -

Fitts PM, Posner MI. Human Performance. Brooks/Cole Pub. Co; Belmont, CA: 1967.

↩ -

Gentile, A. M. (1972). A working model of skill acquisition with application to teaching. Quest, 17(1), 3-23. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00336297.1972.10519717

↩ -

Magill, R. A., & Anderson, D. I. (2007). Motor learning and control: Concepts and applications (Vol. 11). New York: McGraw-Hill. https://www.amazon.com/Motor-Learning-Control-Concepts-Applications/dp/0078022673/ref=sr_1_6?ie=UTF8&qid=1530050653&sr=8-6&keywords=richard+magill

↩ -

Schmidt, R. A. (1975). A schema theory of discrete motor skill learning. Psychological review, 82(4), 225. http://www.hp-research.com/sites/default/files/publications/Schmidt%20(Psych%20Review,%201975).pdf

↩ -

Vereijken, B., Whiting, H., &Beek, WJ (2007). A Dynamical Systems Approach to Skill Acquisition. Pc323-344. https://doi.org/10.1080/14640749208401329

↩

📍1/93 Burwood Rd, Hawthorn, Victoria, 3122

☎️ 03 8851 9890

Copyright © PREP Physio 2020. Read our Terms and Conditions.